Elements

[MYTHOLOGY AROUND PERMANENCE realm]

A broken cell phone with a flickering screen

e-waste was a major external consequence of the digital revolution.

In 2019, a record 53.6 million metric tonnes of electronic waste was generated worldwide. 17.4% of this e-waste was collected and recycled. As time passed, higher consumption rates of electric equipment, devices with short life cycles, and designs with few options for repair propelled the electronic waste stream (United Nations Institute for Training and Research, 2020).

A white and blue surgical mask folded as if discarded

In 2020, an abundant new material appeared floating in the water, hanging from bicycles and trees, sitting on car dashboards, and lying at the side of the road.

The cross-section of a conductor displaying copper and aluminum wires and a bright pink electrical current

Cyberspace influenced how humans engaged and interacted with the environment by connecting computers, digital media, animals, and things as a living system (Colebrook 2014).

A mouldy diary with a black leather cover

A physical record containing data about an arboretum

Place-based practices and the documents they produced reflected what was valued about individual organisms and also exposed shifting values over time (Loukissas, 2016).

A green microchip with gold edges

Decoupling present and future needs:

Human choices in the environment were dispersed in space and time.

Each action made a small opaque contribution to the future of the planet.

A package of margarine with its yellow dye being dispersed

Structures of feeling were rendered and re-organized by the soft and networked architectures of online media (Papacharissi, 2016).

A paintbrush with a blue wooden handle and disheveled bristles

An object used to make slow work. The marks from this tool were dispersed throughout the dig site, a vacuum for new grammars of belonging (Steinhoff, 2017).

A grounded understanding of information begins at the physical and biological level (Bates, 2005). While navigating a realm composed of human-made systems, consider the notion that the human microbiome hosts a variable ratio of 1:1 between human cells and other microorganisms bacteria and fungi (Sender et al., 2016).

[MULTISPECIES RELATIONSHIPS realm]

A green and red apple with a ¼ slice missing

Humans were not the only creatures who lived on the edge of the wild. To some extent, every hive-building, nest-making, lodge-building and burrow-digging creature lived a liminal existence. Yet none of them lived their entire life in the burrow, nest, or hive (Bringhurst & Zwicky, 2018).

A burning $1,000 000 Hell Bank Note

Emerging rituals prompted reciprocity.

A selection of mundane and sacred objects whose values were determined by more-than human beings, were burned for ancestors such as fish, rodents, and small birds. These ceremonies were a means of connecting to familiar and distant ancestors as well as to the land.

A yellow and brown speckled snow apple wrapped in styrofoam padding to prevent bruising

A holistic and multidimensional understanding of the breadth and depth of an animal’s engagement in labour was eventually identified as a type of subsistence work that kept the planet alive (Blattner et al., 2020).

Two bananas ripening from yellow to reddish-brown

Consciousness and perception among animal species evolved throughout hundreds of millennia. Human sentience was one of numerous forms of animal awareness (Shepard, 1997).

A small watercolour painting: light brown and blue washes on a scrap of paper

Representations of the wild continued to proliferate in online networked spaces, even as the buzzing and chattering offline grew conspicuously silent (McCormack, 2019).

A fragment of glazed concrete with smooth weathered edges

A disenchantment of technology and a re-enchantment of non-human nature generated a paradigm shift. Ecocentric ethics counteracted fragmented experiences of the wild often displayed through cell phones and computers (Maxwell & Miller, 2012).

A round piece of concrete with a teal glaze

A decolonial shift from viewing the land as private property, towards an understanding of the land as home to nonhuman neighbours, prompted the realization that the land was not a commodity but rather a gift and a library (Kimmerer, 2013).

An eggplant with grey mould

The 2020 document, A People’s Orientation to a Regenerative Economy, characterized feminist reproductive labour as skilled work that sustained both human society and nature itself. This regenerative economy was guided by community governance and ownership of work and resources (United Frontline Table 2020).

A broken piece of concrete

A gift grew inherently as it was shared. This notion was difficult to grasp in societies whose values were derived from the ownership of private property (Kimmerer, 2013).

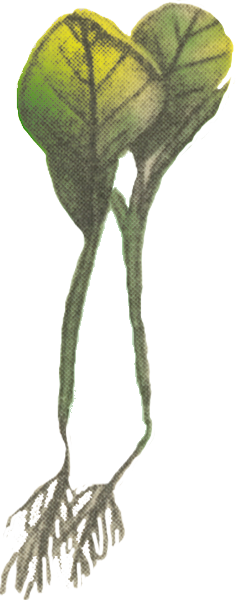

A spinach plant with two yellowing leaves and exposed roots

The earth was situated as a moral reference point. The act of thinking like an ecosystem brought individuals closer to disobedience from both cultural and biological late-capitalist paradigms (Bringhurst & Zwicky, 2018).

a greyish brown centipede

A common disregard towards other-than-human species was offset by a relational set of discourses and practices around empathy, sympathy, and fellow feeling between people, environments, and objects (Hobart & Kneese, 2020).

A bug-eaten leaf turning from red to brown

The principles of cooperation and responsibility were extended to the animals, earth, forests, and seas. No commons would be possible without the refusal to base life and reproduction on the suffering of others (Federici, 2012).

The human-environment system is articulated by various interconnected relationships. The notion of autonomy as an essential process in the self-creation of living systems is coupled with an understanding that humans inhabit a symbiotic system looping within other lifeworlds (Haraway, 2008).

[A MORE-THAN-HUMAN VANTAGE POINT realm]

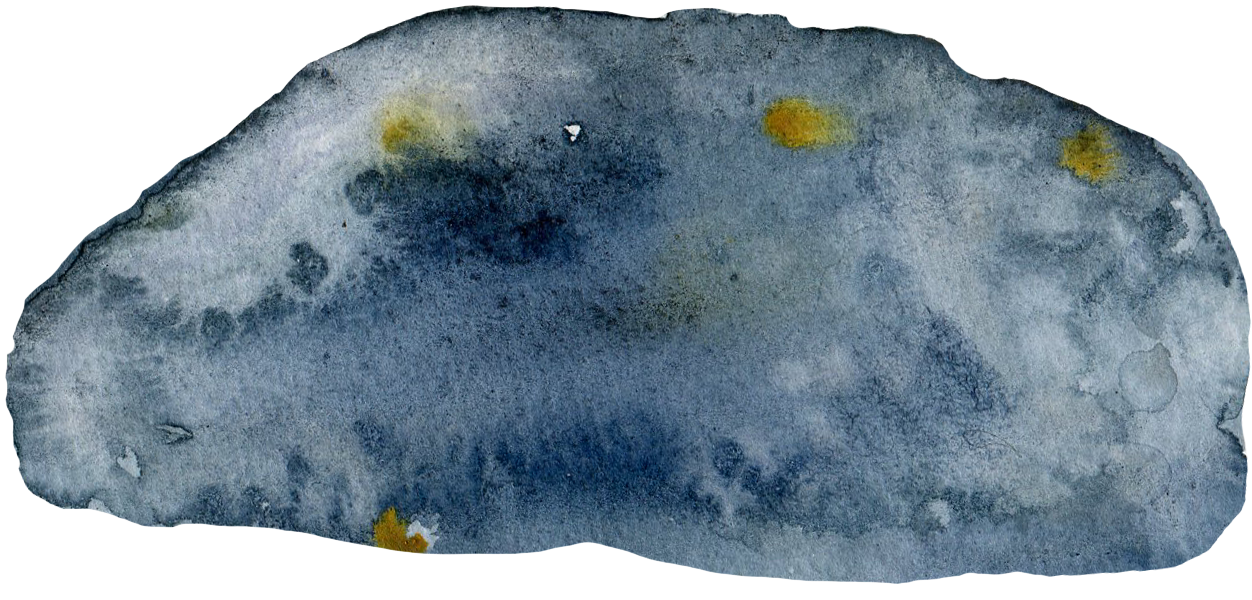

A blue-grey meteorite

Although users of the web were less aware of the physical space of the internet (brick, mortar, metal trailers, electronics containing magnetic and optical media, and fiber infrastructure), human conditions were apparent through the mediation of political, social and economic access points (Noble, 2018).

White and yellow eggs with hatching brown insect larvae

Wild animal engagement through self-controlled, individual, and collective forms of subsistence and care work eventually constituted a form of social reproductive labour called ,.‘Ecosocial Reproduction’ (Blattner et al., 2020).

An orange caterpillar

Bringing animals into the political sphere required attentiveness to nonhuman animal languages, translating what had been gleaned to their representative structures. Humans were encouraged to listen and to exercise care (Meijer, 2019).

A white silkworm

Each year, 70 billion animals contributed to a worldwide economy through actions such as producing sustenance and biodegrading waste. These were critical tasks for healthy functioning ecosystems. A posthuman framework demanded social recognition of historically unpaid or underpaid reproductive labour. This included the work of animals such as worms, fish, insect pollinators, vultures and parasites.

A white silk moth cocoon suspended by branches

Care as an affective and connective tissue between an inner self and an outer world offered the visceral, material, and emotional heft toward the preservation of localities such as: selves, communities, and more-than-human social worlds (Hobart & Kneese, 2020).

A cluster of insect eggs

Forest trees were interconnected through subterranean fungal networks, a web of survival and reciprocity that benefited the trees, fungus, soil and extended to other earthly beings (Kimmerer, 2013).

A round blue-grey rock

Influenced by technical advancements, a human’s temporal sense overlooked the intrinsic deep-timescales of the earth. As conceptions of time sped up, so too did the decomposition of earth’s capital such as the layers of gasses in the atmosphere (Bjornerud, 2020).

A matte black beetle

Nationalism was obscured by winds and waters that knew no boundaries. Gratitude was relocated when speaking to the natural world as a member of the democracy of species. (Kimmerer, 2013).

A white larva

Although they were often close by, earthworms lived independently, and did not cohabit with humans. As human activity influenced the habitat and lives of worms, new multispecies policies reinforced a respect for the interests of worms on how the earth was used.

A cluster of pulsing insect larvae

Multispecies neighbourhoods generated intimacy but also sanctioned respectful distances between animal communities. For instance, earthworms were understood as both neighbours and sovereign communities (Meijer, 2019).

A red and brown meteorite with flecks of gold

Using the grammar of the earth rocks evolved from nouns to verbs, an evidence of processes. The growth of a mountain belt, a volcanic eruption--rocks were witnesses to events that unfolded over long stretches of time (Bjornerud, 2020).

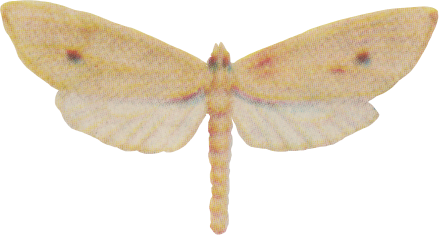

A reddish-brown moth with long hind legs

Animals were often so obscured under the verbiage of power and capital that they briefly disappeared from view (Blattner et al., 2020).

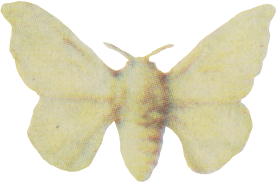

A beige moth with black spot on each wing

The grammar of animacy:

In the wild, humans became audience to conversations in languages of other frequencies (Little Bear, 2016).

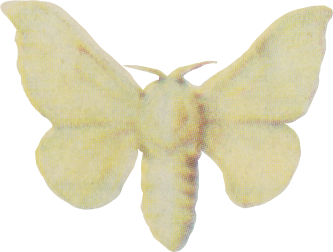

A Grey moth with black wingtips and a flared tail

The world was structured as a neighbourhood of nonhuman residents, a communion of subjects. Métis anthropologist Zoe Todd affirmed that the places humans inhabited and the experience of moving through time were perpetually shaped by more than human beings (Todd, 2018).

A furry light-yellow moth

The Animal Computer Interaction (ACI) manifesto displayed a confidence in techno-utopianism. The manifesto defined ACI’s benefit to both animals and humans as the use of technology that enabled animals to work and communicate with humans (Mancini, 2011).

A furry light-yellow moth

An Indigenous framework positioned habitats and ecosystems as societies with inter-species treaties and agreements through ethical structures of ecosystems. Mohawk and Anishnaabe researcher Vanessa Watts described a practice of reciprocity by identifying non-human beings as active members of society (Watts, 2013).

Two muscle shells opening to reveal a pink opalescent interior

The notion of becoming an integral part of nature rather than merely an observer of nature was cited from various forms of Indigenous traditions and pedagogy. Nonhuman animals and human-environmental relations were embedded in every aspect of life. Practicing reciprocity, care, and tenderness towards more-than-human beings was a method of centering these nonhuman relations (Todd, 2018).

An aquatic slug with a white body and black spots

Animals of all kinds engaged in media technologies through multifaceted structures of animal-networks. The ecological effects associated with online infrastructures ultimately resulted in a digital embodiment of animals that obscured alternative modes of relationality towards the physical wild (Berland, 2019).

A light-yellow rock with specks of blue and brown

Human-environmental relations were embedded in every aspect of life.

The wisdom of other animals was apparent in the way that they lived. Animals taught by example.

“They’ve been on the earth far longer than we have been, and have had time to figure things out. They live both above and below ground, joining Skyworld to the earth”(Kimmerer, 2013).

A white butterfly with black wingtips

Learning the pronouns of the living world:

Adopting a grammar of animacy led to new methods of survival in the world(Kimmerer, 2013).

A white butterfly with black wingtips and two black spots

In Native ways of knowing, humans were often referred to as ‘the younger brothers of Creation’ as they had the least experience with how to live and thus the most to learn. Teachers among the other species offered guidance (Kimmerer, 2013).

A light green leaf with a pulsing green caterpillar eating the centre

No species of placental mammal lived more than a few million years. Coming to the realization that the planet too was mortal, humans planned to maximize their future. Taking a broader vernacular view that included the nieces and nephews of their descendants, they began thinking not just as individuals--or even as a species (Bringhurst & Zwicky, 2018).

An infinite variety of non-communicating and reciprocally exclusive animal worlds jointly compose the earth (Uexküll, 2010). The natural systems realm moves beyond an anthropocentric vantage point by focusing on the frequencies of other-than human beings (Little Bear, 2016).